Maria is Pregnant: How a Venezuelan couple used TikTok to navigate three-thousand miles north

(Maria está Embarazada)

André Salkin 4/5/24

Maria Rivas and Jose Fuentes, La Colaborativa Shelter, Chelsea MA

This past February, José Fuentes and wife Maria Rivas decided to leave their home of Monagas, Venezuela to travel roughly three-thousand miles north to apply for asylum at the U.S. border.

The young couple made preparations made preparations – planning the route, (with the help of a TikTok series) gathering materials, saying goodbyes to friends and family, and knowing how physically challenging the journey would be, getting a medical checkup.

They were healthy, but there was complicated news. Maria was pregnant with a baby girl.

They were left with a decision: raise a family in crisis, or undergo one of the most dangerous journeys on Earth while pregnant.

A week later they bribed Venezuelan officials one hundred US dollars to cross the border into Colombia.

A week later they bribed Venezuelan officials one hundred US dollars to cross the border into Colombia.

・・・

In Colombia, the couple had no trouble from officials. They walked on foot, periodically sleeping on the side of the road until Cúcuta, where they got on a bus to Necoclí, a hub for migrants traveling north.

“You get there and all at once there are people who come and tell you, ‘Look, I am a guide. I am going to charge you 500 dollars per person to take you through the jungle.’ But it’s a lie. It’s a scam. It’s human trafficking,” said José.

In Neoclí, they paid $175 each for ferry passage to Acandí, a Colombian town bordering the jungle on a ferry specialized in transporting migrants. They paid $175 per ticket – a price more than four times higher than the $40 fee listed online for the 1.5 hour trip.

Acandí is one of the main entry-points for migrants to begin the through the Darien Gap. The couple arrived, stocks up on provisions, and purchased two bracelets – costing $50 each.

The bracelets, yellow and orange plastic bands, are like those used to identify event goers at music festivals, or water parks. But these bracelets distinguish between those who can enter the jungle from those who can’t.

An hour’s motorcycle ride got the couple to the border of the jungle where they arrived at a farm – now converted into a camp for receiving migrants. There, camped in family tents, were ‘two to three thousand’ migrants, all wearing yellow and orange bracelets.

When the sun rose, a trumpet sounded, and the thousands of camp inhabitants readied themselves to begin the 106 mile on-foot journey through the Darien Gap.

There were two more camps after the first – each converted farms – and each lying about a day apart along overgrown but easily discernible trails. The camps acted as nightly checkpoints between trail sections with relative security for resting and stores to restock on supplies.

Having money for the bracelet and extra supplies made the jungle relatively safe, said José – the most difficult feature being the terrain of the jungle itself.

“Everyone thinks it's just one jungle,” José said. “No, actually, there are two jungles. The part of Colombia, and the part when you enter Panama. And the border between Panama and Colombia is not a road border or anything. There are two jungles close together. Nothing else.”

No flag, no checkpoint, just a 216-mile-long invisible line wherein the trails, food vendors, and rest points of Colombia devolve into the violent hellscape the Darien Gap is known for.

“The other people that came from the jungle split up. They either go very fast, or very slow. And you can't start waiting for other people because the objective is to get out as soon as possible. So the groups become smaller – ten people, fifteen people, nothing more,”

“But that's where the disaster starts,” he said.

・・・

Candles,

Tent,

Cleaner,

Clothes,

Sweet bread,

Tuna (six cans),

Medicine,

Backpacks (two),

Smartphone,

Bug spray,

Machete,

$1000 (hidden across various places)

And finally, a gift from José’s parents: two shirts, each bearing the family names.

Of the six cans of tuna to last them throughout the jungle, they gave three away to children in need of food. Maria ate three. José ate none.

“But there is a moment when you have nothing to help. There is a moment when you are in the jungle and can not call someone to give you something. There is no entity, no organization to help, nothing. There you are alone. Alone, alone, alone.”

If Maria had already given birth, José said, “I would have left her with the child and I would have come alone. Because in the jungle I saw so many, so many children – drowning, malnourished, dehydrated. I mean, the parents expose the children there to many bad things. My daughter – I wouldn’t let her go through that.”

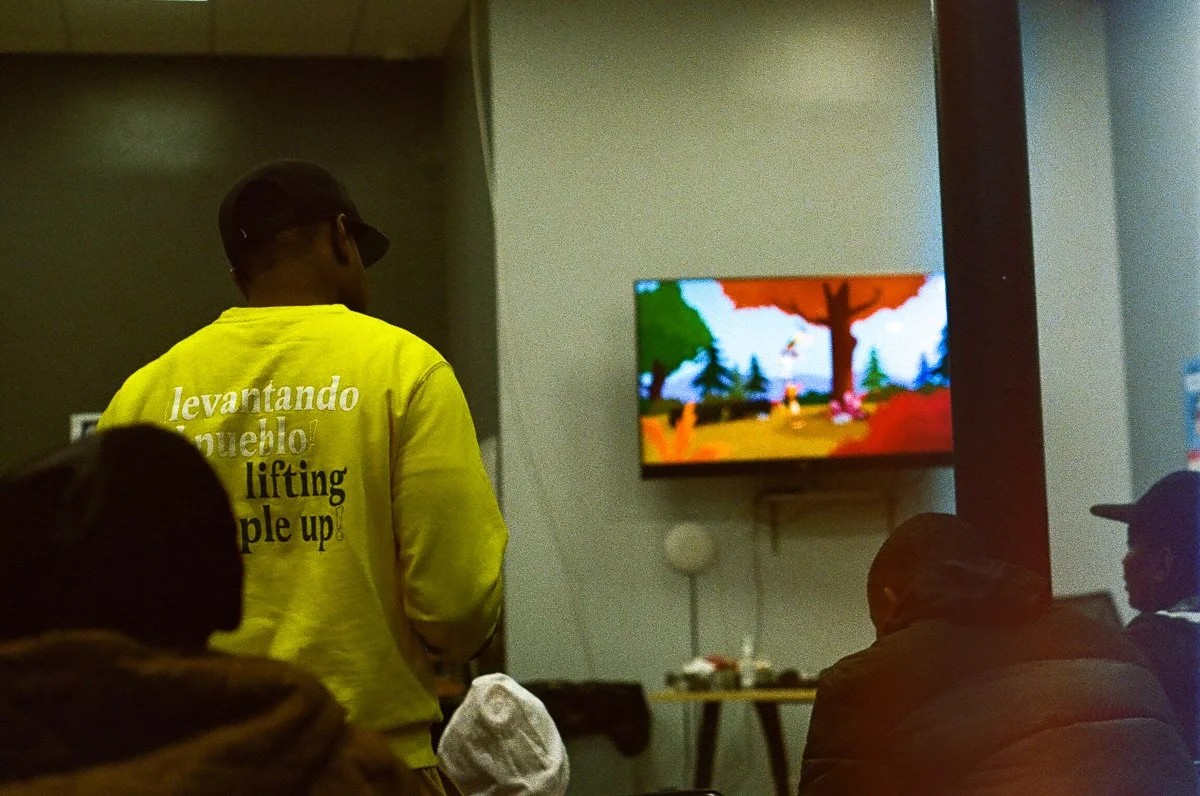

Easter at La Colaborativa Food Pantry, Chelsea MA.

Easter at La Colaborativa Food Pantry, Chelsea MA.

“The mind of a child is so powerful that when there is a circumstance of danger, they see it as play, they see it as fun. They passed through the water, they got dirty with mud, they were happy. But up to a certain limit.”

The Panama Jungle is a different experience. Drinking water and food became near-impossible to come by. Their group could only move during the day because at night, flashlights brought unwanted attention. Trails became a loosely-connected network of handkerchiefs around trees. Green for good, blue for water, and red for danger – marking smuggling and trafficking routes.

But there was no safe trail of the Panama Jungle, and there was no bracelet that could grant safe passage. Being found by the groups that roam the jungle meant a range of things – at best, being offered goods at scam prices, and at worst, falling victim to one of the many gangs formed to take advantage of passing migrants through acts of stealing, murder, and sexual violence.

“In the group I was in, they were wounded. They were drowning, but they were saved. We stayed [in the Panama jungle] for two and a half days. But other groups – those that took seven days to get out– they were seen dead, they were seen fallen, they were seen raped.”

After two-and-a-half days of travel, their group arrived at a Panama guard camp where apathetic Panamanian officials airlifted one woman with a broken leg, refusing to let her family accompany her in the helicopter.

Leaving the camp, the jungle became slightly less dangerous. Ferrymen offered canoe passage over two rivers with deep rapids, where, “You have to take out the water with a pot. Because the water gets in. And if you don't take out the water, all the people drown.”

・・・

From there it’s not far to Bajo Chiquito, the first town outside of the jungle. “All you want to do is eat, eat, and eat, but all the food is inedible.” From there you either pay $40 to get a bus ticket to Costa Rica, or work for two weeks to have the ticket subsidized.

Except the bus didn’t bring them to Costa Rica – only close enough to pay $20 for another few bus tickets to finally reach the border.

Unlike the previous nations, in Costa Rica, “they try to make all migrants pass quickly.” There were camps with beds, providing meals and beds for up to “two to three thousand people.” It was also there that Maria received medicine and prenatal care from a Doctors Without Borders site, and after a short stay, they paid $60 for the bus ticket through Costa Rica.

They followed a path outlined by a TikTok creator who had successfully immigrated, José said.

“[The TikTok series] was precise,” said José. “Not a hundred percent, because all the scenarios are different. The prices are always changing. And it's not for less, it's always for more. Here you have to pay, here it will be dangerous. He explained all that. He explained the orange trees, and that if you go there early in the morning, people come out with guns.”

The ‘orange trees’ are referencing the Nicaraguan orange farms that served as an impromptu border customs checkpoint for passing migrants. It’s one of many tolls, both official and unofficial, outlined in the TikTok series, along with transportation, danger, and rest points.

The “legality” of these tolls, checkpoints, and services is irrelevant. Someone in uniform carrying a gun is demanding payment? It doesn’t matter if they’re a corrupt official or a cartel member. Migrants are forced to pay the toll regardless. A toll which is only increasing in prices as these various groups greater realize the opportunity to siphon funds from migrants in transit.

From Nicaragua through Mexico, the path resumed this earlier pattern of exploitation by a mix of cartels, local enterprise, and government officials.

José and Maria, with about thirty others, slept on streets, in supermarket backrooms, and in church pews as they traveled by bus through Mexico, stopping at the towns and safehouses outlined by TikTok.

“The fear is that you're sleeping and someone comes and hurts you or kidnaps you or something. That's the fear. That's it.”

After a total of two months since crossing the Venezuelan border, the couple and their group arrived at a town near the U.S.-Mexico border and paid a guide to bring them across. Three people in their group drowned crossing the river. After entering the U.S, the couple was received by Border Patrol, put in a processing center, given a court date for an asylum hearing, and allowed free travel throughout the U.S.

Having heard about the state’s services for migrants, they bought a ticket to Boston.

・・・

After arriving, the couple was processed into the Massachusetts system, and placed into two temporary centers – a day shelter in Chelsea, and a night shelter in Cambridge.

Easter at La Colaborativa Food Pantry, Chelsea MA.

Around 10:30 AM, an elementary schoolbus carrying those from the Cambridge shelter arrives at the La Colaborativa Emergency Migrant Day Shelter in Chelsea. Formerly dedicated to aiding the homeless, the Broadway St. shelter was converted in February to prioritize migrant services. It comes as a result of a state-funded initiative to provide for migrants, which subsidizes La Colaborativa to provide legal services, language classes, meals, childcare, and help in submitting housing applications and work permits.

José and Maria lived in this system for around a month, being driven back and forth between the Cambridge and Chelsea centers. José volunteered at La Colaborativa while they waited for their work clearance and housing application to go through. Between jobs at the center, he would stop by to see Maria and say something to make her laugh before returning to work.

Easter at La Colaborativa Food Pantry, Chelsea MA.

“You go to the jungle. You enter into a mental crisis, and well, when you arrive here, there’s another shock because we don't have work. We don't have a stable situation. And here in Massachusetts there are many organizations, but none of them provide the services they should,” Fuentes said.

Easter at La Colaborativa Food Pantry, Chelsea, MA

La Colaborativa stands out though, according to Maria, who said the day-shelter feels uniquely personalized. Especially compared to the Cambridge night-shelter, which Maria said serves meals so inedible that it was common among the Cambridge-Chelsea group to forgo lunch entirely, and save their one La Colaborativa-provided meal for later at the night-shelter.

“At the end of the day, we're an organization that always tries to do more with less,” said Aidan Kaminer, Economic Development Coordinator at La Colaborativa. “We may not have as much funding for this site as some other organizations do, but we have a higher level of success because we make it really clear that you're not just our clients. We're helping you be successful and feel empowered as members of the community.”

Thanks to a La Colaborativa-sponsored job search, José applied for and secured a job at McDonalds – a massive win for the college-educated chemical engineer. He remained working and volunteering until finally, he and Maria received more permanent housing. Thanks, in large part, to the nearly $1b set aside in the state’s 2024 budget to fund the homeless families and emergency shelter housing programs.

Despite the Chelsea site’s successes, and state initiatives to provide for migrants, the U.S.’s current migrant asylum system is failing, according to Jeffrey Thielman, CEO of The International Institute of New England, a nonprofit specializing in migrant resettlement across New England.

Failing, Thielman says, partly due to an uncertain legal framework being used to resettle and support these migrants, who are technically called ‘humanitarian parolees,’ under the 1980s federal legislation. A federal framework which the government is calling to be implemented on the state level – a solution which makes way for widespread underfunding and unclear policy direction.

La Colaborativa, Chelsea MA.

“I want the United States to be a home for people who are looking for a new life,” said Thielman. “Apart from the humanitarian reason for welcoming people, there's an economic reason because there aren't enough jobs that are filled in our economy right now. We need folks here. We need people to come. But, that said, the federal government should be chipping in and giving us some support systems to do this work. It can't just let folks into the country without some financial support for them.”

Until their asylum hearing, the future is still unknown for people like José and Maria. But for now, a few things are certain. There is food on the table, and the baby is safe.